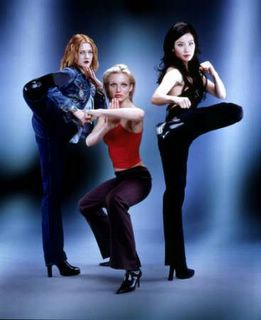

Charlie's Angels

Nowhere does Hollywood’s culture of deception more clearly manifest itself than on those television talk shows in which stars tell about their movies. The point of this media exercise, at least for the studios releasing the movies, is to fuse the celebrity stars with their fictive movie characters (otherwise the stars might focus interest on themselves instead of the movies being opened.) So carefully-designed PR scripts require that the stars "stay-in-character," as Hollywood calls real life play-acting. When it comes to action movies, the scenario typically calls for stars to tell making-of-movie anecdotes that suggest that they, like the heroes they play on screen, perform death-defying feats. Even if the putative perils are an obvious stretch, they can almost invariably count on a suspension of disbelief on the part of their host-interrogator. Consider, for example, the heroics related on MTV by the three lovely stars of Charlie’s Angels: Full Throttle– Lucy Liu, Drew Barrymore, and Cameron Diaz.

The MTV interviewer, JC Chasez began by asking, "Did you guys do any of your own stunts?"

"We did," Lucy Liu ("Alex") jumps in.

"We get to do all these amazing things," Cameron Diaz ("Natalie") adds, describing by way of example how Drew Barrymore ("Dylan") clung to a speeding car going about "35 miles an hour" while "hitting on the hood of the car"– even after her safety cord came undone.

"She’s literally hanging on to the car," Liu explains.

At this point in the story, with Barrymore precariously holding onto the hood with one hand and banging on it with the other, the interviewer asks her excitedly why she didn’t yell, "Cut"?

Barrymore ("Dylan") explains despite the danger to herself, she persevered with the shot because "you get so into the adrenaline and you want to be tough.... my character, Dylan, was trying to stop the bad guy." In other words, she had morphed into Dylan – at least in the PR script.

Now back to reality. Stars may have license on talk shows to fantasize about performing perilous stunts such as hanging off the hood of a speeding car, but on a movie set, no matter how willing they may be to risk their lives and limbs, studios will not permit them to take such risks for two cogent reasons.

First, stars often do not have an opportunity to perform stunts because action movies are not shot linearly. As I explain in The Big Picture: The New Logic of Money and Power in Hollywood, the work is divided between different units that shoot at the same time in different places. The first unit, "principal photography," shoots the stars and other actors (who do so-called "matching shots" that can be blended into stunts); the "second units" shoot the stunts as well as backgrounds that do not require the presence of the actors. In the James Bond movie Tomorrow Never Dies, for instance, this division of labor had 5 different people playing the James Bond character– Pierce Brosnan, the star, was playing James Bond at the Frogmore Studio outside of London, while four stuntmen at four different locations were playing him in stunts. Similarly, In Charlie’s Angels: Full Throttle, the "Dylan" character, was played by Drew Barrymore and stunt women Heidi Moneymaker, a star gymnast, and Gloria O’Brien. (Lucy Liu’s character had 5 players).

A second, and even more compelling reason, is the cast insurance requisites. Even if stars are physically present during the shooting of perilous stunts, the production’s insurers prohibit them from substituting for the stuntmen. Since Harold Lloyd nearly lost two fingers performing his own stunts in 1920, cast insurance has been a sine qua non requisite for a Hollywood movie. If a star is deemed an essential element in a movie– as Liu, Diaz, and Barrymore are in Charlie’s Angels: Full Throttle– and the star becomes disabled, the insurer must cover the resulting loss – which may be the entire investment in the project, which in the case of Charlie’s Angel: Full Throttle was about $120 million. Before issuing such expensive policies– and no Hollywood movie could be made without one– insurers go to great lengths to make sure that actors do not take any risks that could lead to even a sprained ankle or pulled muscle. Their representatives analyze every shot in the script for potential risks and scrutinize the stars’ prior behavior on and off the screen. (See, for example, the answer to the Question of the Day on my web site.) Once the production starts, they also station hawk-eyed agents on the set to make sure that the stars are not put in harm’s way. They might require, for example, that a star standing on a stationary car be held by two safety men (masked in blue spandex so they can be digitally deleted from the final movie.) Even if a director or producer were willing to risk injuring a star, the insurer would not allow it. So stars, as much as they might enjoy performing their fantasies, cannot do dangerous stunts for movies.

For the most part, stars do not tell these tall tales of daredevil

adventurism on television out of either personal dishonesty, vanity, or egoism. It is their job to play a character in publicity appearances, just as it is the job of studios to hype their movies. Nor do others in these Hollywood productions– even if they were not bound by contractual restrictions on disclosures, or "NDAs"– have reason to demystify such off-screen fictionalizing. The subterfuge is part of the system by which studios, talent agencies, music publishers, licensees, and others create, maintain, and profitably exploit the stars’ public personalities. The more interesting question: why entertainment journalists, instead of challenging these preposterous claims, act as the star’s smiling attendants on this organized flight from reality? The answer: deception is a cooperative enterprise. By suspending their disbelief, the entertainment journalists get the stars on their programs.