Monday, June 06, 2005

Thursday, June 02, 2005

Friday, May 20, 2005

The Blur Between Fact And Fiction

Michael Douglass

Can the New York Times distinguish fact from fiction any longer?

Consider a front page story today (May 20,2005) stating "Just as corporate raiders represented the Wall Street of the 1980's (think of Gordon Gekko) and mutual fund managers were the icons of the 90's (Jeffrey N. Vinik, who ran the Fidelity Magellan fund, was a minor celebrity), the lawyers who keep companies in compliance with increasingly tough regulatory laws have become a new prototype of the financial district." Unlike Jeffrey Vinik, however, Gekko is not a real person. Played by Michael Douglas in the 1987 movie Wall Street, he is a fictional creation of writer-director Oliver Stone. Stone, himself a master of the art of blending fact and fiction in movies, say he modeled the character after Ivan Boesky. That may be true, but Boesky was not a corporate raider. He was a crooked money manager, who bought inside information for cash, traded illegally on these secrets, and went to prison for it.

The New York Times reporter, Jennifer Steinhauer, may have been innocently misled into thinking Gordon Gekko was a real corporate raider by CNN’s program Moneyline which repeatedly used a film clip in the 1990s from the movie in which an immaculately dressed Gordon Gekko (Michael Douglas) intones "Greed is good" to illustrate news reports of corporate corruption. Moneyline's decision to use such fictional clip for its news coverage was, appropriately, part of an even bigger greed-is-good corporate deal in which Warner Brothers (which produced Wall Street) paid CNN (which was acquired by its corporate parent from Turner Entertainment ) to hype the licensing values of its movies. The result, as is demonstrated by the New York Times, is that fictional images such as Gekko come to stand for real events.

Saturday, May 14, 2005

Paranoia For Fun and Profit

Michael Moore

Michael Moore proved yet again that funnctional paranoia could be both fun and lucrative. By the end of April 2004, he'd finished making Fahrenheit 9/11 but had no American distributor. Mel Gibson's Icon Productions rejected the project back in April 2003. (Moore claims he had a signed contract before Gibson acquiesced to White House pressure. Icon executives deny any such contract existed.) Moore then went to Harvey Weinstein at Miramax. Weinstein agreed to back the movie and signed a contract with Moore to acquire the rights. But in order to distribute the movie, Weinstein still needed the approval of his superiors at Disney. Although he does not discuss this publicly, Weinstein's contract explicitly prohibits Miramax, a wholly owned subsidiary of Disney, from distributing any film that's vetoed by the Disney CEO. When CEO Michael Eisner exercised his veto in May 2003, Miramax, though it still held the rights to the film, could not distribute Fahrenheit 9/11.

By the time Eisner told Weinstein of his decision, the Miramax head had already given Moore $6 million from Miramax's loan account. Weinstein agreed that this advance was to be "bridge financing" that he would recover when he sold off the film's distribution rights. To make sure there was no misunderstanding, Disney's Senior Executive Vice President Peter Murphy, who was also at the meeting, wrote Weinstein a letter on May 12, 2003, affirming that this money was "bridge financing" and that Weinstein had agreed to dispose of Miramax's interest in the film.

For Moore, this $6 million in "bridge financing" was more than enough to make Fahrenheit 9/11. He acquired most of the footage from television film libraries at little, if any, cost and did not pay any of the on-camera talent (except for himself). On April 13, 2004, after Weinstein saw a rough cut, he went back to Eisner and asked him to reconsider his year-old decision not to distribute Fahrenheit 9/11. After getting a report on the content, which included footage from such sources as Al Jazeera and Al-Arabiya television, Eisner saw no reason to change his position. He again declared that Disney wouldn't have anything to do with the movie.

With the presidential election heating up, Moore needed to get his movie into theaters. Although Weinstein had told Eisner and Murphy that he planned to sell the film's distribution rights after it was screened at the Cannes Film Festival, Moore had a more expedient strategem. On the Fahrenheit 9/11 DVD, Moore says he resolved to get the film seen in America "by hook or by crook." His hook was censorship.

On May 5, 2004, the New York Times ran a front-page article headlined "Disney Is Blocking Distribution of Film That Criticizes Bush." The story included the sensational charge that Eisner "expressed particular concern that [choosing to distribute Fahrenheit 9/11] would endanger tax breaks Disney receives for its theme park, hotels and other ventures in Florida, where Mr. Bush's brother, Jeb, is governor." The source for this allegation was Moore's agent, Ari Emanuel. Two days later, Moore claimed on his Web site that Disney's board of directors rejected Fahrenheit 9/11 "last week." In fact, the Disney board had not made such a decision in 2004—the project had been vetoed in 2003.

Moore's excursion from reality proved a boon at Cannes. On May 22, 2004, the Cannes jury defied putative efforts to censor Moore by awarding Fahrenheit 9/11 the prestigious Palme d'Or. Moore now had a golden palm in his hand and the media at his feet—with more free publicity than any Hollywood studio could afford to buy, Fahrenheit 9/11 now stood to rake in a fortune. And Disney, which still controlled the movie's rights through its subsidiary Miramax, now got to decide who was going to profit from it.

Disney had some experience dealing with Miramax's hot potatoes. Rather than distributing the controversial Kids and Dogma, Disney allowed Miramax founders Harvey and Bob Weinstein to buy the films back and set up short-lived companies to distribute them. But those potatoes were as small as they were hot. In the case of Fahrenheit 9/11, Eisner wasn't about to let the windfall escape into the Weinstein brothers' pockets. Nor could Disney take the PR hit that would result from backtracking and distributing the movie itself.

Eisner's solution: Generate the illusion of outside distribution while orchestrating a deal that allowed Disney to reap most of the profits. Here's how the dazzling deal worked. On paper, the Weinstein brothers bought the rights to Fahrenheit 9/11 from Miramax. The Weinsteins then transferred the rights to a corporate front called Fellowship Adventure Group. In turn, that company outsourced the documentary's theatrical distribution rights (principally to Lions Gate Films, IFC Films, and Alliance Atlantis Vivafilms) and video distribution rights (to Columbia Tristar Home Entertainment).

Because of the buzz and prestige attached to Fahrenheit 9/11, Harvey Weinstein extracted extremely favorable terms from these distributors, about one-third of what distributors typically charge. Their cut amounted to slightly more than 12 percent of the total they collected from the theaters. As a result, Fahrenheit 9/11's net receipts—what remains after the distributors deduct their percentage and their out-of-pocket expenses (mounting an ad campaign, making prints, dubbing the film)—would be much higher than those of a typical Hollywood film.

Fahrenheit 9/11, now an event, took in more than $228 million in ticket sales worldwide, a record for a documentary, and sold 3 million DVDs, which brought in another $30 million in royalties. After the theaters took their share of the movie's gross (roughly 50 percent) and distributors deducted the marketing expenses (including prints, advertising, dubbing, and custom clearance) and took their own cut, the net receipts returned to Disney were $78 million.

Disney now had to pay Michael Moore's profit participation. Under normal circumstances, documentaries rarely, if ever, make profits (especially if distributors charge the usual 33 percent fee). So, when Miramax made the deal for Fahrenheit 9/11, it allowed Moore a generous profit participation—which turned out to be 27 percent of the film's net receipts. Disney, in honoring this deal, paid Moore a stunning $21 million. Moore never disclosed the amount of his profit participation. When asked about it, the proletarian Moore joked to reporters on a conference call, "I don't read the contracts."

What of Disney? After repaying itself $11 million for acquisition costs, it booked a $46 million net profit, which Eisner split between two subsidiaries, the Disney Foundation and Miramax. While it was far less than Disney made on children's fare such as Finding Nemo, it was not a bad outcome. The Weinstein brothers also made a multimillion-dollar profit. They had a deal with Disney that contractually entitled them to a bonus of between 30 percent and 40 percent of the net profits on any film that they produced—in this case, that came out to about $8 million per brother. But Michael Moore had perhaps the happiest ending of all. Not only had he made $21 million, he already had a sequel in preproduction—Fahrenheit 9/11 ½.

Sunday, April 03, 2005

Dowdy Intelligence

Maureen Dowd

In a scathing ad hominem attack on the Commission on Intelligence Capabilities in the New York Times today, Maureen Dowd protests: "It is absurd to have yet another investigation into the chuckleheaded assessments on Saddam's phantom W.M.D. that intentionally skirts how the $40 billion-a-year intelligence was molded and manufactured to fit the ideological schemes of those running the White House and Pentagon." She then implores, "Please, no more pantomime investigations."

Despite such ridicule from Dowd, the nine-person bipartisan Commission is not without credentials and the capability of intelligent speech. Co-chaired by Governor Charles S. Robb, the former Democratic Senator from Virginia, and Judge Laurence Silberman, who serves on both the U.S. Court of Appeals and U.S. Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court of Review, its members include Walter Slocombe, President Clinton’s former Undersecretary of Defense, Judge Patricia Wald of the International Criminal Tribunal at the Hague, Senator John McCain, Republican from Arizona, and Charles Vest, the President of M.I.T. It had unprecedented access to all the documents used by the Intelligence Community in reaching its judgments about Iraq’s WMD programs, including what no journalist has ever seen: the chain of documents ranging from raw operational traffic produced by intelligence operators to finished intelligence products culminating in the President’s Daily Brief. Its 60-man staff interviewed hundreds of officials involved in producing and analyzing these documents. Aside from US intelligence reports, the Commission also reviewed the highly-classified assessments of British, Australian, and Israeli Commissions.

Doth Dowd protest too much? As it turns out, she has a a most compelling reason for scorning the Commission: its findings expose her own repeated misrepresentations of the event.

Consider Dowd’s amazingly smug assertion: "We all know what happened... Ahmad Chalabi conned his neocon pals, thinking he could run Iraq if he gave the Bush administration the smoking gun it needed to sell the war. Suddenly Curveball appeared, the relative of an aide to Mr. Chalabi, to become the lone C.I.A. source with the news that Iraq was cooking up biological agents in mobile facilities hidden from arms inspectors and Western spies."

Dowd here is partly correct: "Curveball"– an Iraqi engineer who defected to Germany– was a fabricator. According to the Commission, he provided false information that seriously misled the CIA to conclude Iraq had biological weapons. But she is wrong that Curveball was a product of the Bush administration. He defected during the Clinton Administration. He defected to Germany in 1999, and his (mis)information was passed by the Germans first to the DIA and then to the CIA a year or so before Bush was President. His false data on Iraq biological warfare went to Clinton's policy makers in 2000 and was included in the CIA’s revised 1999 National Intelligence Estimate (NIE). As he refused to (ever) meet with CIA or other US intelligence officers, the CIA could not squeeze more out of him than he gave to his German debriefers. Dowd’s assertion that "Suddenly Curveball appeared...." during the Bush administration is therefore demonstrably false. That Dowd repeated it in two columns-- March 31st and April 3rd-- after the facts were revealed in the Report gives her serial status.

The Commission also found that there was not a shred of evidence showing Curveball was influenced by Chalabi (as Dowd claimed in her March 31st column) or his INC organization. On page 107, the Commission says: "the CIA’s post-war investigations were unable to uncover any evidence that the INC or any other organization was directing Curveball to feed misleading information to the Intelligence Community. Instead, the post-war investigations concluded that Curveball’s reporting was not influenced by, controlled by, or connected to, the INC."

Moreover, whereas Dowd describes Chalabi as providing "the smoking gun" to the Bush Administration, the Commission concludes " In fact, over all, CIA’s post-war investigations revealed that INC-related sources had a minimal impact on pre-war assessments."

The Commission also undercuts an idea that has run amok among Dowd, as well as journalists at Newsweek and the New Yorker, that the CIA's faulty analysis of intelligence was the result of political pressure. On the contrary, the Commission found "Analysts universally asserted that in no instance did political pressure cause them to skew or alter any of their analytical judgments. We conclude that it was the paucity of intelligence and poor analytical tradecraft, rather than political pressure, that produced the inaccurate pre-war intelligence assessments."

The Commissions’ report is well worth reading (especially for journalists reporting on the issue). It shows that the enormous intelligence failure went beyond fabricating defectors. Technical intelligence, which CIA officials in the 1980s promised would provide an electronic Maginot Line against deception, proved to be just as vulnerable to error as human intelligence. Indeed, according to the report, it was the satellite imagery from Iraq that led to the staggering mistakes about Iraq’s chemical weapons. The problem lies in the elusive nature of "intelligence" itself. Whether obtained from humans , communication interceptors, or satellite cameras, the data requires interpretation. Unlike marbles, which can be lined up by size or color, each fragment of intelligence must be selected and placed in a scheme that exists in the mind of the beholder. In this case, the mind of the beholder, the CIA, was at least temporarily deranged between 1998 and 2003.

Sunday, March 27, 2005

Rise Of The Tube Moguls

Brad Grey Toasts Jeff Bewkes

A common thread runs through the appointments of Robert Iger as CEO at Disney, Sir Howard Stringer as Chairman of Sony, Tom Freston as Co-President of Viacom, Brad Grey as CEO od Paramount, Gail Berman as President of Paramount, Jeffrey Bewkes as President of the Time Warner Entertainment & Networks Group , and Peter Chernin as President of the Fox Entertainment Group. They are all former top TV executives.

The ascendency of the tube moguls should not come as a surprise– at least not to readers of The Big Picture. What used to be the movie business, centered in "movie houses," has been transformed into the home-entertainment business, centered around TV sets. Old Hollywood studios–prior to 1948– owned or controlled movie houses; New Hollywood studios– or their corporate parents– own or control television outlets. In fact, they own all six broadcast networks in America, almost all the principal cable networks in America, and most of the Pay-TV channels in America.

Underlying this transformation is a singular reality: most of the adult population no longer goes to the movies on a regular basis. As late as 1948, over two-thirds of Americans went to the movies weekly. Now barely 10 percent of Americans go in an average week (and, even in this sliver of the population, most of the frequent movie-goers are teenagers.) Where did the audience go? On any given night, over 90 percent of the American population is at home watching something on a television set. Naturally, Hollywood followed that mass audience home.

The numbers, which I reveal in Table 1 of The Big Picture, tell the story: ticket sales from theaters, which had provided all the studio revenues in 1948, provided less than 20 percent of the studios’ revenues in 2003 . Instead, home entertainment– including television, Pay-TV, DVD, and videos– provided more than 82 percent of the studios' revenues . Further, whereas as the high costs of print and advertising eat away most, if not all, of theatrical revenues, the studios retain the lion's share of the home entertainment revenues.

These lucrative home entertainment earnings have transformed the way Hollywood operates. Theatrical releases, despite the blinding allure they hold for the media, now serve essentially as launching platforms for its products for the home market, much like the runways at money-losing fashion shows establish brands for downstream consumer markets.

With New Hollywood's takeover of the television now all but complete-- see my X-Ray of the 6 major studios' media holdings-- the line of succession now runs to the gatekeepers of its El Dorado: the tube executives

Monday, March 21, 2005

Send In The Aliens

Milla Jovovich

Furthering the Midas formula for New Hollywood, Twentieth Century Fox arranged in 1996 for the then governor of Nevada, Bob Miller, to dedicate Nevada’s Highway 375 as an "Extraterrestrial Highway" on which aliens would be granted safe haven when they landed their UFOs. The studio then unveiled a beacon on it near the town of Rachel, Nevada. This monument, according to the Fox news release, pointed to "Area 51"–where the U.S. military operates "a top secret alien study project." In fact, there is no such military base or "Area 51", but Fox assumed it had license to stretch the boundaries of reality for the opening of Independence Day– a Fox movie that, not unlike the news release, depicted "Area 51" as the U.S. government base for alien spacecraft. So while its beacon had only problematic navigational utility to any visitors from alien heavens searching for "Area 51," it had great value in luring entertainment journalists by the busload along the now official Extraterrestrial Highway to the putative periphery of the non-existing "Area 51." These investigative junkets (helped along with the usual studio-provided terrestrial gift bags) resulted in hundreds of news stories about the alien sanctuary.

The reason that Fox went to such lengths to establish Area 51 is that the mining of the paranoid fantasy about government machination to conceal space invaders from the public produces gold in the form of licensing rights for the New Hollywood. Steven Spielberg deserves much credit for developing the mother lode of this El Dorado. In his enormously-successful Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977), the US government is so deeply involved in concealing the alien abductions that it stages a fake nerve-gas attack to hide its transactions with extraterrestrials. The deception pays off when, in an inspired ending, the aliens exchange the humans they have been abducting for experimental purposes for a busload of American astronauts. Spielberg expanded on the theme with E.T.: The Extra-Terrestrial (1982), which not only broke box-office records around the world, but opened up the universe of merchandise licensing which heretofore largely been the preserve of Disney. He also produced the franchise, Men in Black (in which the government not only shelters ETs but systematically erases the memories of civilians exposed to alien visitors) and the miniseries Taken about alien abductions (its tag line: "Some secrets we keep. Some are kept from us.")

These Spielbergesque fantasies neatly fit the requisite in New Hollywood for movies that could serve as launching pads for the raft of other products– including videos, games, toys, TV spinoffs and rides– that now kept it afloat. So others followed suit. Fox, for example, used The X-Files television series to help establish the Fox network.

Ironically, in promoting a view of governments as paternalistic institutions that create elaborate illusions to shield citizens from developments with which they cannot cope, studios may be extrapolating from the strategies they themselves use to dupe the public. What else is the Extraterrestrial Highway but a brilliant con job? The political logic of Hollywood may seem other-worldly, but, as The Big Picture explains, there is a decided method in its madness .

Sunday, March 13, 2005

The Money Shot

William Safire

The lucidity prize for summing up my entire 396-page book in a succinct sentence goes to master wordsmith William Safire. In his column in today’s New York Times Magazine, he writes: "In The Big Picture: The New Logic of Money and Power in Hollywood, the investigative author Edward Jay Epstein holds that what used to be the movie business, centered in "movie houses," has been transformed into the home-entertainment business." That transformation, in a nutshell, is the key to understanding the New Hollywood.

Even though today's Hollywood studios may have the same names, logos and back lots as their Old Hollywood counterparts, they are radically different creatures. The Old Hollywood studios owned movie houses; the New Hollywood studios– or their corporate parents– own television conduits, including all six broadcast networks, all the principal cable networks (including ESPN), and most of the pay-TV channels. The Old Hollywood studios made virtually all their money from the sale of tickets at box-office; the new Hollywood studios make most of their money from licensing products, including movies, TV shows, and videos, for home entertainment. For the extent of the TV windfall alone, see the answer to my Question of the Day.

Underlying this transformation is the reality that most of the adult population no longer goes to the movies weekly. Consider: as late as 1948, over two-thirds of Americans went to the movies weekly. Nowadays barely 10 percent of Americans go in an average week (and most of today's frequent-goers are teens). Today's mass audience-- over 90 percent of the population-- is at home watching something on a television set.

The ineluctable metamorphosis of Hollywood into a provider of home entertainment brought with it a new global logic. For one thing, unlike the movie business, the television business is licensed, franchised, and regulated by government authorities.

If this sea change has remained elusive to the outside world, that is not accidental. The owners of the new Hollywood go to considerable lengths to conceal the breakdown of their cash flows they garner from home entertainment. Once the numbers are known– and I provide the breakdowns in The Big Picture– it becomes clear that all that remains of the Old Hollywood is institutionalized nostalgia, self-generated myths, and an outdated vocabulary.

Tuesday, March 01, 2005

Willful Blindness

"Willful blindness involves the conscious avoidance of the truth"

-- Merriam-Webster Dictionary of Law

In Hollywood reporting willful blindness can be found in the media’s avoidance of any performance measures for moguls that might get undercut "gotcha" personality stories. This eyes-wide-shut practice serves a truly gawkeresque purpose: it allows entertainment journalists to focus on juicy tidbits about the bad manners of moguls while ignoring, or at least holding in abeyance, readily-available facts that might distract their audience from them.

Consider, for example, the field day. or, more precisely, field decade, that the media has enjoyed in its disparagement of Disney’s Michael Eisner. The stories about Eisner’s bad behavior began soon after Jeffrey Katzenberg, Disney’s talented studio chief, left in 1994, intensified after Eisner’s clumsy firing of Michael Ovitz in 1996, and became a veritable feeding frenzy after Eisner got rid of Roy Disney, Walt Disney’s nephew, in 2003. The rehash of items about Eisner's insensitive language (eg. describing Katzenberg as a "midget"), nepotistic decisions (eg. hiring his friend Ovitz), back-stabbing (eg. firing Ovitz) and rich payoffs (eg., honoring the compensation committee’s negotiated $140 million settlement with Ovitz) gradually coalesced into a media morality play: how Eisner's "dark side" led to Disney’s near downfall. To keep the story plausible, entertainment journalists kept their eyes wide shut to the numbers that showed that Eisner, even with the "dark side" that their moral compasses located, had transformed Disney into a huge financial success.

Willful blindness conveniently allowed these journalists to miss the most obvious measure of performance: the valuation of Disney by the stock market. Here are the actual figures: in 1984, when Eisner took over Disney, the (split corrected) Disney share price $1.20, giving Disney a market value of only $1.7 billion; in 1994, when Katzenberg left, the share price was $12.90, Disney had a market value of $18.6 billion; today the share price is $28.5, giving the company a market value of $55.8 billion. So under Eisner, his bad manners and questionable pay offs not withstanding, Disney’s market value has increased $54 billion. Even taking inflation into account between 1984 and 2005, the company increased 18 times in value under Eisner. In view of this enormous business success, it is not surprising that Fortune’s 2005 poll of 10,000 business executives rated Disney as the most admired company in the entertainment industry. These executives evidently valued good performance over bad manners.

Eisner achieved the $54 billion increase in the company’s value not because of his "dark side" but because he recognized that Disney’s future would be in home entertainment– not movie theaters– and, to move Disney in this direction, boldly bought Capital Cities/ABC in 1996 for $19 billion. Disney acquired not only 10 ABC television stations in the biggest advertising markets and the ABC network, but 80 percent of ESPN which turned out to be a huge money-machine. With this coup, Disney moved to the forefront of home entertainment, which is now the heart (if not the soul) of the new Hollywood. As I demonstrate in my book The Big Picture, the logic of money and power behind the new Hollywood is not always transparent. For a closer look at why Disney makes record profits even when its movies bombed at the box-office, see the answer to my Question of the Day on my web site.

Wednesday, February 23, 2005

Lighting Hollywood's Camera Obscura

Hedy Lamarr

The screenwriter William Goldman famously explained Hollywood this way: nobody knows anything. He is right– up to this point. The decisions of Hollywood studios seem inexplicable to anyone who is not privy to what is perhaps their most carefully guarded secret: the breakdown of the money made from sources other than movie houses. Despite the tsunamis of back-stabbing and self-idolizing anecdotes about mini-moguls that all but drown the entertainment media, there is a Saharan dearth of information about actual cash flows from such after-markets as television networks, cable television, Pay-TV, and DVD sales.

If these numbers are obscure that is not accidental. Studios have no interest in providing a road map to their El Dorado to those who might want to claim a share of the gold, including talent agents, stars, producers, directors, writers, and equity partners. And, as of now, no regulatory agency requires divulging this information. So just as the studios keep their patrons in the dark in movie theaters, they keep their other audiences in the industry– and media– in the dark about the magnitude of these cash flows.

Once the lights go on– and I provide the numbers and breakdowns in The Big Picture– the studios’ decisions not only are explicable but the business model is more relentlessly logical than those of many non-creative industries. They demonstrate that those who ask how the movie industry can possibly make sense are asking the wrong question. There is (no longer) a movie industry, there is an entertainment industry. Consider, for example, Table I, in my book. The ticket sales from theaters, which had provided all the revenues in 1948, provided less than 20 percent of the studios’ revenues in 2003 . Instead, home entertainment in the form of television, Pay-TV, DVD, and videos provided more than 80 percent of the studios' revenues in 2003. This tidal shift reflects this underlying reality: on any given night, less than 2 percent of Americans go to movie theaters while over 95 percent stay home to watch something on TV. Since the advertising and other marketing costs associated with DVD sales and television licensing are minimal, the six big studios earn a veritable ocean of bottom-line profits from this home market. These rich streams, which studios understandably prefer to keep private in their camera obscurae, have transformed the way Hollywood operates. Theatrical releases, despite the blinding allure they hold for the media, now serve essentially as launching platforms for licensing rights, much like the runways at haute couture fashion shows.

Even in the face of this forced march towards home entertainment, there are notable disconnects between the economic and social logic of the Hollywood community. See, for example, the answer to today's Question Of The Day– "Is movie sex an asset or a liability in Hollywood's economy today?"

Saturday, February 19, 2005

Logic of Hollywood

My book has finally made it to the book stores. What is it about? The Big Picture is neither pro nor anti Hollywood: it is a demystification of it. The thesis, as perverse as it may sound, is that there is an underlying logic to today’s multibillion-dollar entertainment economy--and that those who run the industry understand it

The gross misunderstanding most people have about Hollywood proceeds from the assumption that the business is about making movies. Once upon a time, it was: as late as 1948, two-thirds of Americans went to the movies every week and the tickets they bought accounted for virtually all of Hollywood's profits. But the lights blinked out in that universe more than half a century ago, obliterated by the bright blue glow of television.

Today, the big picture is very different. On an average night about 4 million Americans go to the movies, while more than 260 million Americans stay home to watch something-- a program, video, DVD-- on television. Hollywood may continue to pay lip service to its ever-diminishing audience of moviegoers, but it now makes its real money from the home audience. To tighten their grip on it, the studios gradually extended their domain over the entire television industry. All six broadcast networks and most of the commercial cable channels are now owned by the corporate parents of the six big studios-- new Hollywood's sexopoly -- and the studios make most, if not all their money, from that captive home audience. As far as the studios are concerned, the main function of the remaining moviegoing audience-- barely ten percent of the population-- is to help establish a movie in the public’s mind for the all-important home market. To get it, they go after that part of it they can most efficiently find. Happily for the studios, the audience that has proved easiest to find (because they’re home watching TV), lasso (with a barrage of 30-seconds ads) and herd to the multiplexes for big opening weekends is also the primary audience for videos, merchandising tie-ins, and character-driven video games: teenagers. As a result, people under 21 now make up over 62 percent of habitual moviegoers.

Not surprisingly, the creative decisions of the sexopoly are largely driven by the economic necessity of capturing the home audience. But that is not the whole story. There is also a social logic involving awards, prestige, star worship, publicity-mongering, power, and even the impulse to make a work of art, which, though less tangible, also informs the Big Picture.

Book reviews

Sunday, February 13, 2005

Playing The Reality Card

Leslie Parrish

The political values of today’s Hollywood often surface in its selection of stereotypes for movie heroes and villains. Such choices are particularly clear in remakes of past movies that substitutes new villains for outdated ones. Consider, for example, Paramount’s recent remake of the 1962 classic, The Manchurian Candidate. The original movie, directed by John Frankenheimer and based on a novel by Richard Condon (an ex-Hollywood publicity man), is both a thriller about a hypnotized assassin and a satire of political paranoia. The evil protagonist is the Soviet Union, whose nefarious agents, with the help of the Chinese Communists, abduct an American soldier in Korea and turn him into a sleeper assassin. When Paramount decided in 2004 to remake the movie as a straight psychological thriller, with the military abduction transposed from Korea in 1950 to Kuwait in 1991, it obviously needed a new resident evil to replace the defunct Soviet Union. Even though the U.S. was battling the Iraqi forces of Saddam Hussein in Kuwait at that time, Demme chose not to make the Iraqis or Islamists the villain of his movie because, as he explains in his DVD commentary, he did not want to "negatively stereotype" either Arabs or Muslims. Neither Saddam Hussein nor Iraq is even mentioned in the film.

Whom, then, did Demme enlist to play the heavy in his remake? What evildoer can be safely "negatively stereotyped" as an enemy of America in today’s Hollywood? Answer: hedge-fund managers. These lily-white, impeccably dressed corporate executives man the helm of the Manchurian Global Corporation, a multibillion-dollar equity fund that is planning a "regime change" in America so it can secure more government contracts. Not only do the fund’s technicians rewire the brains of abducted soldiers, but they implant them with false memories of al-Qaeda-type terrorists so that, if caught, they will blame Muslim extremists rather than the fund managers for their crimes.

The challenge for Paramount was in building a "reality envelope" that gave the movie’s demonization of corporate executives a more convincing connection to actual events. Warner Brothers had previously met this challenge by making an arrangement with CNN (which its corporate parent owns) that resulted in the cable network’s news program, such as Moneyline, showing the scene from Oliver Stone’s movie Wall Street in which the immaculately dressed financier Gordon Gekko (Michael Douglas) intones "Greed is good" to illustrate news reports of corporate corruption.

Paramount-- which does not own CNN-- found a more imaginative way to breach the fluid boundary between movies and television news for its resurrected Manchurian Candidate. It created a counterfeit web site for the Manchurian Global Corporation. Since it nowhere identified the site as fabricated (and went so far as to provide a fictional address and phone number to hide its own role in the site’s design), any person who found the site via Google or another search engine would have reason to believe that the Manchurian Global Corporation was a real equity fund with huge biotech investments in such projects as the genetic decoding of Alzheimer's disease.

Although Paramount’s ingenious deception may violate ICANN rules against using false information when registering a domain– a Paramount executive defended the fraud by pointing out that even if it involved "pushing the reality envelope," it is an integral part of show business.

There is indeed a hoary tradition in the movie business of such reality enhancement, as I explain in my book The Big Picture: The New Logic of Money and Power In Hollywood. Throughout the era of the studio system, studios made it a practice to invent off-screen lives– including fictional romances with co-stars –– for the stars they had under contract. They then relied on the fan magazines, newsreels, and gossip columnists they controlled to disseminate these newly burnished images. Even though today's studios no longer own the stars, they enjoy an even greater dominion over the entertainment media. Their corporate parents own all six television broadcast networks, as well as almost all the major cable networks-- a cozy arrangement that further fuses the interests of Hollywood and television.

The new Hollywood’s real-life relationship with the media thus proceeds from a serious commonality of interests. And as Tad Friend insightfully reported in the New Yorker, one of the interests all the players have is in not revealing that commonality. "It is in everyone's interest (except, perhaps, the reader's) to pretend that P.R. consultants are not involved in stories," Friend writes. "It behooves the journalist, because it suggests that he has penetrated a rarefied realm; it behooves the star, because he looks fearless and unattended by handlers; and it behooves the publicist, because it always behooves the publicist if the star is behooved."

Behind this cloak of media invisibility, Hollywood’s armies of publicists are free to plant items that continue to blur the rapidly-eroding line between fact and fiction. One top producer of a national late night talk show observed that "ninety percent of talk show anecdotes are either completely manufactured or improved so significantly that they are basically untrue." Creating fraudulent websites for nonexisting corporations is simply one further stretch of an already-larger-than-life reality envelope.

Saturday, February 05, 2005

Culture Of Deception

Charlie's Angels

Nowhere does Hollywood’s culture of deception more clearly manifest itself than on those television talk shows in which stars tell about their movies. The point of this media exercise, at least for the studios releasing the movies, is to fuse the celebrity stars with their fictive movie characters (otherwise the stars might focus interest on themselves instead of the movies being opened.) So carefully-designed PR scripts require that the stars "stay-in-character," as Hollywood calls real life play-acting. When it comes to action movies, the scenario typically calls for stars to tell making-of-movie anecdotes that suggest that they, like the heroes they play on screen, perform death-defying feats. Even if the putative perils are an obvious stretch, they can almost invariably count on a suspension of disbelief on the part of their host-interrogator. Consider, for example, the heroics related on MTV by the three lovely stars of Charlie’s Angels: Full Throttle– Lucy Liu, Drew Barrymore, and Cameron Diaz.

The MTV interviewer, JC Chasez began by asking, "Did you guys do any of your own stunts?"

"We did," Lucy Liu ("Alex") jumps in.

"We get to do all these amazing things," Cameron Diaz ("Natalie") adds, describing by way of example how Drew Barrymore ("Dylan") clung to a speeding car going about "35 miles an hour" while "hitting on the hood of the car"– even after her safety cord came undone.

"She’s literally hanging on to the car," Liu explains.

At this point in the story, with Barrymore precariously holding onto the hood with one hand and banging on it with the other, the interviewer asks her excitedly why she didn’t yell, "Cut"?

Barrymore ("Dylan") explains despite the danger to herself, she persevered with the shot because "you get so into the adrenaline and you want to be tough.... my character, Dylan, was trying to stop the bad guy." In other words, she had morphed into Dylan – at least in the PR script.

Now back to reality. Stars may have license on talk shows to fantasize about performing perilous stunts such as hanging off the hood of a speeding car, but on a movie set, no matter how willing they may be to risk their lives and limbs, studios will not permit them to take such risks for two cogent reasons.

First, stars often do not have an opportunity to perform stunts because action movies are not shot linearly. As I explain in The Big Picture: The New Logic of Money and Power in Hollywood, the work is divided between different units that shoot at the same time in different places. The first unit, "principal photography," shoots the stars and other actors (who do so-called "matching shots" that can be blended into stunts); the "second units" shoot the stunts as well as backgrounds that do not require the presence of the actors. In the James Bond movie Tomorrow Never Dies, for instance, this division of labor had 5 different people playing the James Bond character– Pierce Brosnan, the star, was playing James Bond at the Frogmore Studio outside of London, while four stuntmen at four different locations were playing him in stunts. Similarly, In Charlie’s Angels: Full Throttle, the "Dylan" character, was played by Drew Barrymore and stunt women Heidi Moneymaker, a star gymnast, and Gloria O’Brien. (Lucy Liu’s character had 5 players).

A second, and even more compelling reason, is the cast insurance requisites. Even if stars are physically present during the shooting of perilous stunts, the production’s insurers prohibit them from substituting for the stuntmen. Since Harold Lloyd nearly lost two fingers performing his own stunts in 1920, cast insurance has been a sine qua non requisite for a Hollywood movie. If a star is deemed an essential element in a movie– as Liu, Diaz, and Barrymore are in Charlie’s Angels: Full Throttle– and the star becomes disabled, the insurer must cover the resulting loss – which may be the entire investment in the project, which in the case of Charlie’s Angel: Full Throttle was about $120 million. Before issuing such expensive policies– and no Hollywood movie could be made without one– insurers go to great lengths to make sure that actors do not take any risks that could lead to even a sprained ankle or pulled muscle. Their representatives analyze every shot in the script for potential risks and scrutinize the stars’ prior behavior on and off the screen. (See, for example, the answer to the Question of the Day on my web site.) Once the production starts, they also station hawk-eyed agents on the set to make sure that the stars are not put in harm’s way. They might require, for example, that a star standing on a stationary car be held by two safety men (masked in blue spandex so they can be digitally deleted from the final movie.) Even if a director or producer were willing to risk injuring a star, the insurer would not allow it. So stars, as much as they might enjoy performing their fantasies, cannot do dangerous stunts for movies.

For the most part, stars do not tell these tall tales of daredevil

adventurism on television out of either personal dishonesty, vanity, or egoism. It is their job to play a character in publicity appearances, just as it is the job of studios to hype their movies. Nor do others in these Hollywood productions– even if they were not bound by contractual restrictions on disclosures, or "NDAs"– have reason to demystify such off-screen fictionalizing. The subterfuge is part of the system by which studios, talent agencies, music publishers, licensees, and others create, maintain, and profitably exploit the stars’ public personalities. The more interesting question: why entertainment journalists, instead of challenging these preposterous claims, act as the star’s smiling attendants on this organized flight from reality? The answer: deception is a cooperative enterprise. By suspending their disbelief, the entertainment journalists get the stars on their programs.

Wednesday, February 02, 2005

The Sexopoly and Antitrust

Rabbit or Duck?

In response to my last web-log entry (January 31) about the six movie studios’ secret revenue data, I received an out-of-the-blue email from an extremely well-respected antitrust economist (a man who, because he once worked for the movie industry, prefers to remain anonymous), who asks, "Has this data-sharing relationship ever been questioned by authorities?" He goes on to note: "US antitrust officials generally look at such scenarios with a suspicious eye. . . . Generally, when competitors share sensitive business data--without disclosing these data to the public (analysts or public at large)--there needs to be some procompetitive purpose, such as enforcing safety standards. Absent such procompetitive justifications, such scenarios are usually investigated for any evidence of cartel behavior."

The secret data about markets is not the only information the six studios share. They also conveniently use the same private market researcher, the National Research Group (NRG), which supplies each of its clients with a weekly "Competitive Positioning" report. As is explained in more detail in my book The Big Picture: The New Logic of Money and Power in Hollywood, from the report’s breakdown of upcoming movies’ relative appeal to different age, sex, and ethnic groups, studios can see how their films are likely to fare against competing films appealing to the same audience groups. Studios can then coordinate their films’ release dates to avoid competing for the same all-important opening-weekend audience.

To be fair, even if, as Adam Smith famously said, "people of the same trade seldom meet together, even for merriment and diversion, but the conversation ends in a conspiracy against the public," data sharing is not necessarily anticompetitive. It depends, as the Department of Justice and Federal Trade Commission Antitrust Guidelines for Collaborations Among Competitors assert, on just what kind of information is being shared:

"The Agencies recognize that the sharing of information among competitors may be procompetitive and is often reasonably necessary to achieve the procompetitive benefits of certain collaborations; for example, sharing certain technology, know-how, or other intellectual property may be essential to achieve the procompetitive benefits of an R&D collaboration. Nevertheless, in some cases, the sharing of information related to a market in which the collaboration operates or in which the participants are actual or potential competitors may increase the likelihood of collusion on matters such as price, output, or other competitively sensitive variables. The competitive concern depends on the nature of the information shared" (pp. 15-16).

Anticompetitive collusion or procompetitive collaboration? Like the famous "Rabbit or Duck" illusion, it’s all in the eye of the beholder– and in this case, the Bush Administration is the beholder who counts. Given the current climate of acquiescence to corporate cooperation, it seems extremely unlikely that the sharing of secret data by Hollywood’s sexopoly will be a candidate for investigation anytime soon.

Indeed, in another regard, the six studios may themselves be victims of a restraint of trade by what is today the country’s greatest monopsony: Wal-Mart. Wal-Mart, which writes the single biggest check to Hollywood each year for videos and DVDs (which it both rents and sells), has told the studios, according to one top studio executive, that if they dare to move up the release date of their movies on Pay-Per-View to compete with Wal-Mart’s rental business, they do so at the risk of losing critical shelf space in the giant retailer’s stores. For more on this possible monopsony stranglehold--and the man who might break it– see the answer to the Question of the Day on my website today.

Monday, January 31, 2005

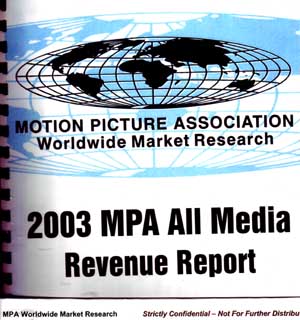

Hollywood-By-The-(Secret)-Numbers

Under the intriguing headline "Video Sales Abroad Are Good News in Hollywood. Shhh," Ross Johnson reports in The New York Times today (January 31, 2005) that the Motion Picture Association (MPA), although it is privy to the studios income from worldwide DVD and VHS sales, will not give out that vital information. An MPA spokesman told Johnson, "Those figures are confidential, and we don't release them." So instead the Times had to rely on a British publication called Screen Digest for the guessestimate that the studios took in $11.4 billion from overseas home-video sales in 2004. Johnson rightly complains "It has always been hard to pry reliable numbers out of Hollywood, even when the numbers tell a happy story."

Ross Johnson is absolutely right about the importance of MPA numbers. They come directly from Fox, Time Warner, Sony, NBC-Universal, Paramount, and Disney, the 6 studios that dominate the new Hollywood . As part of their general principle of keeping their audience in the dark, the studios keep secret from the public-- and even the Wall Street analysts-- the data that accurately reflect the real sources of their earnings. Each of these studios, however, furnishes these precise data, including a detailed breakdown of their worldwide revenues from movie theaters, home video, network television, local television, pay television and pay-per-view– to the Motion Picture Asocciation on condition that they will not be released to any other parties. The MPA then consolidates these cash flows into the MPA All Media Revenue Report which it then circulates back to the studios on a confidential basis. Each studio can then use this common pool of data– the 2003 report is over 300 pages– to compare its own performance, and that of its subsidiaries, to that of the other major studios in 64 different markets. I had access to all these reports between 1999 and 2004 for my book The Big Picture: The New Logic of Money and Power in Hollywood. They helped answer a crucial question: how do the studios actually earn their money?

Now, there is no reason for the home-video market to remain a secret or even a press guessestimate. In 2003– the last full year that the MPA reported the studio data– the studios (and their subsidiaries) earned $18.9 billion from the world home video market. Of that $18.9 billion, $7.68 billioncame from overseas markets. Foreign DVD sales provided $5.52 billion, foreign VHS $2.16 billion. Ninety percent of those foreign earnings came from just 10 countries. (For a more complete breakdown, see Tables 2 and 3 in the Deal X-Raying section of my website).

Why shouldn't Hollywood-by-the numbers be public knowledge?

Sunday, January 30, 2005

The Hollywood Sexopoly

There’s no business reported like show business--coverage of which usually consists of star-driven anecdotes, idiosyncratic examples, and anachronistic measures of performance, enlivened with punning headlines such as "Incredible Incredibles Capsize Nemo at the Box-Office." If news of the OPEC cartel were reported in this fashion, its business would be reduced to a series of "boffo" gushers and "megaflop" dry holes– and, no less, in its older fields that no longer produce its real wealth. Perhaps it’s fitting that an industry dedicated to illusion should be covered in such a make-believe way except that the new Hollywood is not just entertainment, it is a vast multibillion-dollar economy ruled by six giants– Sony, Disney, NBC-Universal, Fox, Time-Warner, and Viacom. And what is neglected by Show Biz stories about star assignments, PR hype wars, astounding digital-effects, and box-office grosses is the reality of how the Hollywood sexopoly cashes in on the world entertainment economy.

Consider, for example, just television-- a medium that the old Hollywood attempted to strangle in its crib in the 1940s by denying it movies. The studios' numbers here, even though they are not in the domain of entertainment journalists, tell a remarkable story.

First, there is global Pay-TV. While the six big studios do not disclose to the media what they earn from Pay-TV in 2003, they (and their subsidiaries) scored $3.37 billion from licensing their movies to it . Of that total, $1.59 billion came from sales to Pay-TV channels in the US, such as HBO and Showtime; and the remaining $1.78 billion came from Pay-TV abroad (largely from Rupert Murdoch’s satellite broadcast empire). The studios license most, if not all, their films in "output deals," or multifilm packages, at a fixed price per film. That price – currently about $8 million per film in America– is not dependent on the film’s box-office performance. (When, in earlier days, Showtime tied the fee it paid for Ghostbusters to its box-office performance, it proved disastrously expensive for Showtime.) As a rule, then, a box-office failure generally commands the same price as a success. For many foreign output deals, a film is required to have played in theaters for a minimum period (which is why studios sometimes have token openings for movies in a handful of theaters).

How profitable is the studios’ take on their Pay-TV deals? In 2004, the $3.37 billion the six studios got far exceeded what they cleared from the box office after they had deducted their print and advertising costs. (Bear in mind that with Pay-TV deals, all advertising expenses are paid by the Pay-TV channel, and, of course, there are no prints.)

In addition to Pay-TV, the Big Six sell their movies, cartoons, and television programs to the six American broadcast networks – CBS, NBC, ABC, FOX, UPN, and WB– all of which are now cozily and conveniently owned by the studios’ own corporate parents. In 2003, the networks paid their corporate siblings licensing fees of slightly over $4 billion for the rights to broadcast their products. Over three-quarters of this money was for television series and made-for-TV movies that obviously have no relation to the box office. Even in the case of the movies they license, networks weigh many factors aside from a film’s success at the box office. For one thing, they must consider the durability of its appeal, since it will not be broadcast until between two and five years after its theatrical release. More important, they have to consider whether their advertisers, as well as government regulators, will consider it suitable for a prime-time audience. Controversial films by Oliver Stone that proved successful at the box office, such as JFK and Natural Born Killers, for example, were turned down by the networks. They now also have to take into account their connection to the studios that are their corporate siblings. ABC, for example, which is owned by Disney, not surprisingly licensed the lion’s share of its films and shorts from Disney.

Finally, the studios have a cash cow in licensing the films and television programs in their libraries to local television and cable stations around the world. In 2003, library sales earned $5.5 billion for the six studios. Since library sales do not begin until a half-decade after movies are out of theaters– and are often part of output deals– their box-office performance is only loosely related to what they earn for the studios.

In all, the six studios took in about $14 billion in 2003 from a television complex that their corporate parents largely control. And this is only one part of Show biz's unshown side . For more on this cozy if not incestuous liaison of the sexopoly, see the answer to my Question of the Day today on my web site.

Monday, January 24, 2005

Gross Misunderstanding

The Tomb Raider

Today, like every Monday, newspapers ritualistically published the week’s box-office grosses as if it were important news. Once upon a time, when Hollywood studios owned the theaters and carted away locked boxes of cash from them, these box-office numbers meant something. Nowadays, as dazzling as the "boffo, " "socko," and "near-record" figures may still seem to the media, their main import is to help further a gross misunderstanding about the real business of the New Hollywood. That misunderstanding takes at least three different forms.

First, the box-office results seriously confuse outsiders about who earns what. The reported "grosses" are not those of the studios but those of the independently owned movie houses. The movie houses take these sums, keep their share (or what they claim is their share)--which, along with the so-called "house allowance," can amount to over 50 of the original box-office total--and remit the balance to the studios’ distribution arms, which then deduct the out-of-pocket expenses involved in marketing the movies.

Consider, for example, Disney’s action "success" Gone in 60 Seconds, which had a "boffo" $242-million box-office gross. From this impressive take, the theaters kept $129.8 million, and remitted the balance to Disney’s distribution arm, Buena Vista. After paying mandatory trade dues to the MPAA, Buena Vista was left with $101.6 million. From this sum, it repaid the marketing expenses that had been advanced– $13 million for prints so the film could have a wide release; $10.2 million for the insurance, local taxes, custom clearances, and other logistical expenses; and $67.4 million for advertising. So what remained of the nearly quarter-billion-dollar reported "gross" was a paltry $11 million. (And that did not include the $103.3 million that Disney had paid to make the movie in the first place .)

Second, box-office results primarily reflect neither the appeal of the actual movies–nor their quality–but the number of screens on which they are playing and the efficacy of the ad campaign in getting people to go to these theaters. If a movie opens on 30 screens, there is obviously no way it can achieve the results of a movie opening on 3,000 screens. And how do studios motivate millions of moviegoers–mainly under 25–to go to 3,000 screens on an opening weekend to see a film no one else has yet seen and recommended? With a successful advertising campaign. Studios spend $20-30 million on TV ads because their market research shows that those ads are what can create its crucial opening-weekend teenage audience. To do that, they typically blitz their target audience, aiming to hit each viewer with 5 to 8 30-second ads in the two weeks prior to a movie’s opening. If the ads fail to trigger the right response, the film usually "bombs," in Variety’s hyperbolic judgment; if the ads succeed, the film is rewarded with "boffo" box-office numbers.

Third, and most important, the gross "news" confuses the feat of buying an audience with that of making a profit. Last year (2003), the cost of prints and advertising for the opening of a studio film in America totaled, on average, $39 million, which was $18.4 million more per film than studios recovered from box-office receipts. In other words, it cost more in prints and ads--not even counting the actual costs of making the film--to lure an audience into theaters than the studio got back. So while a "boffo" box-office gross might look good in a Variety headline, it might also signify a boffo loss.

Ironically, what is obscured by the media’s relentless fixation on box-office grosses is the true genius of the New Hollywood: its profitable takeover of the much more lucrative global home- entertainment economy. Disney’s corporate earnings, for example, soared fifty percent in the first half of 2004 despite an almost unbroken string of box-office failures, including Hidalgo and The Lady Killers in March, Home on the Range and The Alamo in April, Raising Helen in May, and Around the World in 80 Days and King Arthur in June. What were Disney’s real money spinners: think ABC, The Disney Channel, ESPN, Disneyland and (still) Mickey Mouse.

Movies, of course, are still part of the big picture–and always will be–but the true art of Hollywood is, more and more, the art of the deal, not the picture. And unlike the ubiquitous box-office numbers, the mechanisms of the deal--involving government subsidies, tax shelters and artful presales–rarely appear on the public’s radar. Even underlying the otherwise silly Paramount movie Lara Croft: Tomb Raider is a minor masterpiece of a deal. To see how Paramount raked in $87 million through financial alchemy before it even green-lighted that film, see the answer to my Question of the Day. For a fuller account of how and why Hollywood keeps its audience in the dark, see my coming book The Big Picture: The New Logic of Money and Power in Hollywood.

Thursday, January 20, 2005

Rupert's Radical Strategy

Rupert Murdoch

Rupert Murdoch, who revolutionized British journalism in 1986 by moving his four newspapers in the middle of the night from Fleet Street– London’s newspaper center for over 100 years– to Wapping in the docklands ( crushing two powerful unions in the process), is not a man to do things in small measure. He currently controls, among other things, a major movie studio (Twentieth Century Fox), a television network (Fox Television), 30 cable channels (including Fox News, FX, and Fox Sports), and an armada of satellites that beam movies, sports, and programs to television sets on five continents.

Business Week reports that he is ordering 20 million Tivo-type Digital Video Recorders. Does he now plan to revolutionize the way the world gets its movies on television? For Murdoch’s radical strategy, see the answer to my Question of the Day (Today)

Tuesday, January 18, 2005

The Role of Intellectuals

Woody Allen

Whatever the role of intellectuals in American politics, they clearly have a role in the American cinema-- even if it is only a walk-on. For clear proof, see my List 43.

Monday, January 17, 2005

The Golden Globes Informational

Hilary Swank

Since my new book concerns the social as well as economic logic of Hollywood, I tivo-ed the Golden Globes Awards last night on NBC. If this star-wrangling informational did not exist, NBC might have had to invent it to compete with ABC’s Oscar Awards. Fortunately, for NBC, an otherwise obscure group calling itself the Hollywood Foreign Press Association (HFPA) had invented this award-ceremony in 1944 during a free lunch in the 20th Century Fox commissary. Although its dozen or so "members" were mainly refugees in the Land of Nod (as Sam Spiegel called LA). The German occupation of their homelands had made most of them correspondents without a country, but they loved movies. At this point, Twentieth-Century Fox’s ingenious studio head Darryl F. Zanuck saw that they offered a highly-valued product in Hollywood: awards for studio movies. Since the Academy of Arts & Sciences had passed over his studio's Song Of Bernadette for the "Best Picture" Oscar in 1943), why not accept the "Best Picture" award-- as well as Best Director" and Best Actress-- from the Hollywood Foreign Press Association (although the "association" had not yet put together enough money to design the "Golden Globes.") So, with a little largesse from the studios, another annual Award ceremony-- and opportunity for product placement-- was born.

In short order, the HFPA came up with a slew of other awards that appealed to studio chiefs: "Best Film for Promoting International Good Will," "Best Film Promoting International Understanding," "Best Non-Professional Acting," "Hollywood Citizen Award," "Ambassador of Good Will," and a special award for "Furthering the Influence of the Screen" (which went to the Hindustani version of Disney's Bambi.) With them, it promoted lavish dinners at celebrity hangouts including Ciro's, the Coconut Grove and the polo lounge of the Beverly Hills Hotel.

For a while, it was run by Swedish twin brothers; Gustav and Bertil Unger, who were tap dancers. Gustave wore his monocle in his right eye, Bertil in his left. Reportedly, they picked winners on the basis of who they could get to show up.

But despite the fun, the enterprising group only began to make real money when Ted Turner elected to televise its informational in the 1980s, a gig taken over by NBC in 1996 (which paid the HFPA roughly $3 million a year for the broadcast rights.)

Nowadays it is of no matter that the 82 members who vote the awards are mostly free-lance writers and photographers with day jobs or that they have little, if any, connection with the Hollywood community. As the Hollywood Reporter observed "The studios couldn't care less whether the awards are decided by isolated Benedictine monks in the Himalayas or angels on high, at least not since the Globes have evolved into a tremendous marketing tool." As such, it offer scripted speeches by stars, promotional clips from movies, and nostalgic eulogies to some 20 million viewers. And by this time the value of public self-congratulation has become so inculcated in the Hollywood culture that one producer carpingly complained to me, "These ceremonies have taken over our social life. Almost every week we get into our formal gear, push through a gauntlet of paparazzi to get to some ballroom, give ourselves awards for everything from movies to lifetime achievements, and then applaud ourselves." Nevertheless, Hollywood’s star troopers suited up last night for yet another black-tie award ceremonies. All part of the Big Picture.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)